OCTOBER 2006

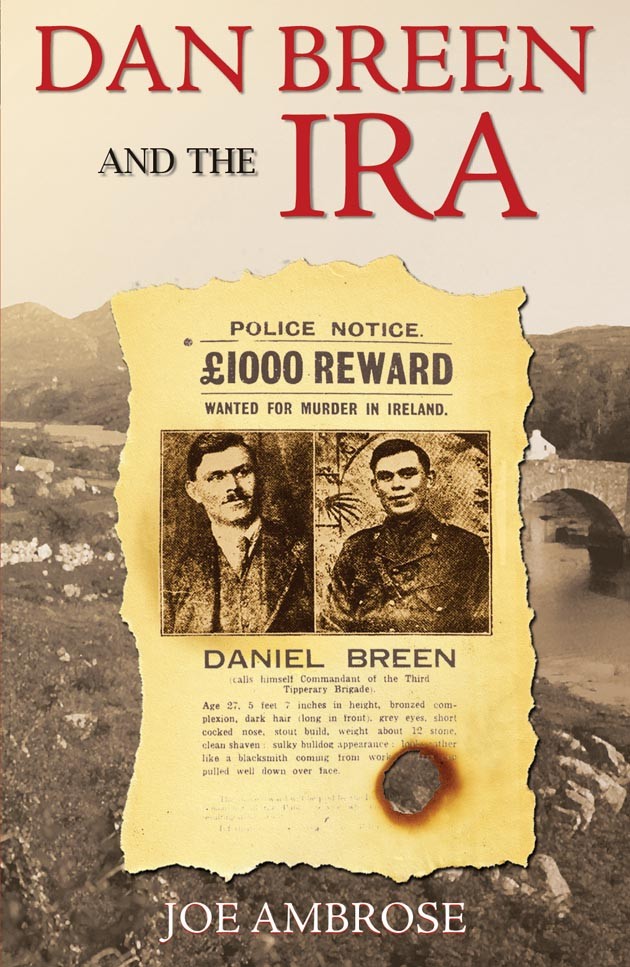

Extract from Dan

Breen and the IRA

byJoe Ambrose

Note: With his comrades in the IRA Dan Breen helped kick start the Irish War of Independence in 1919; he played a major role in that war and the ensuing Civil War. ‘Dan Breen and the IRA’ (Mercier Press) – an extract from the book appears below – is the story of Breen and the 1916-1923 IRA leaders told in their own words and from their point of view. When the shooting was over Breen went to Prohibition America, ran a speakeasy, and locked horns with Al Capone. In later life he drifted to the left and was active in the anti-Vietnam War movement and the leftist Republican Congress.

Dan Breen runs like a ragged thread through the history of Ireland in the twentieth century. He remains, to this day, one of the most famous and contentious IRA leaders of his generation.

The Irish may owe him a certain debt of gratitude but the Irish are cranky by nature; they sometimes like to take pot shots at iconic characters like Breen.

The Irish are also a post-colonial people, incessantly told what to do and think by international opinion makers working in publishing, broadcasting, and the arts. A colorful and curious array of naysayers, soothsayers, and academics – not to mention pseudo-scholars fighting their own private Wars on Terror – devote entire Amazon rain forests of paper to debunking some simple facts of narrative history concerning Ireland’s War of Independence. They’ve taken to their task with gusto and occasional aplomb, undermining complex mythologies which have grown up around the likes of Breen, Michael Collins, and Cork IRA leader Tom Barry. Trying to dismantle the reputations of these rural lads of humble origin, they’ve sought to create post-modern mythologies of their own from which 1916-23 guerrilla leaders emerge as political deviants from some imaginary, civilized, democratic norm, frantically in league with nebulous forces of evil, indifferent to mandate or morality.

The simple storyline and sequence of events to be found in the memoirs, statements, interviews, and correspondence of those participating in that IRA campaign, is closer to the truth. Those leaders emerge from their own testimonies as heroic figures. They undoubtedly saw themselves that way. They thought they were ‘a grand collection of men.’ What did the rest of the people in their country make of them? The answer to that question is as simple as the storyline and does not need the interpolation of researchers or commentators. Those who supported the notion that Ireland would only get independence from Britain through armed struggle thought them terribly heroic. Those who thought that ‘freedom’ could be achieved by purely democratic means – and those who favoured union with Britain – often thought of them as thugs with blood on their hands. One’s assessment of the 1916-23 leaders has everything to do with one’s own political prejudices and nothing to do with the history of that combat.

Breen, more than most others, is

regularly filed away under ‘Thug with Blood on His

Hands.’ This is largely because of the ongoing

controversy surrounding his first major guerrilla outing

as part of the gang behind the 1919 Soloheadbeg police

killings, but it is partially because of the forthright

manner in which he defended that gory exploit for the

rest of his life. Mary Anne Allis – the aunt of his

pal Sean Treacy – called him ‘Breen the

Murderer’ until the day she died. Having witnessed

Breen’s behavior during the Soloheadbeg clash, his

commanding officer Seamus Robinson made a mental note

that he was a man who, ‘should never be put in

charge of a fight.’ A close relative of my own, who

was forever seeing Dan Breen around our family’s

farmyard when she was growing up, said, ‘There was

something dirty about that Dan Breen.’ Rumor had it

that he was illiterate and couldn’t have written his

own book. In fact he wrote vigorously and read

voraciously.

Blame and plaudits were heaped upon Breen all through his life; he accepted the blame and soaked up the plaudits. He said that the policemen he helped kill at Soloheadbeg were, ‘a pack of deserters, spies, and hirelings’ and that, ‘I would like to make this point clear, and state here without any equivocation that we took this action deliberately having thought the matter over and talked it over between us.’

Though he was certainly a radical extremist throughout the war against the British, and though this is his overriding reputation, the Dan Breen who lived on into the era of Kennedy and the Vietnam War was a conciliator and a moderate. Trusted by both sides before and during the Irish Civil War, he did everything in his power to avoid that conflict.

Soloheadbeg remains a political and historical hot potato. It also remains a substantial turning point in the history of modern Ireland. It forced the hand of nascent Dublin-centered urban power elites within Sinn Fein, the IRB, and the IRA.

My paternal grandfather – who was also in the IRA but who took the opposing side in the Civil War – used to say that Breen's memoir, My Fight For Irish Freedom, was the book in which the word "I" was used the most often in the English language. That the book is full of self-aggrandizement, bombast, and bias is beyond question. That it sometimes plays hard and fast with the facts is likely. Seamus Robinson – who was unduly prejudiced against Breen – called it ‘The Great Tipperary Hoax.’

My Fight for Irish Freedom made Dan Breen one of the permanent heroes of the revolution. Compared with the literary – but bookish – guerrilla writings of Che Guevara or Ernie O’Malley it might seem thin gruel but it was written as propaganda. It is hugely successful, Homeric, propaganda.

Dan Breen certainly didn't win his war single handed, and the ego-driven style of his ghost-written book is not replicated in his Statement to the Bureau of Military History in Dublin. The Breen who emerges from that recollection was very political, very realistic, and impressively harsh. That Dan Breen painted a picture of a collective Tipperary leadership determined, all on their own if needs be, to remove Ireland from the British Empire.

In February 1919 the Third Tipperary Brigade of the IRA – the sons of small farmers and labourers – issued a proclamation instructing the British to quit South Tipperary under pain of death. The decree was greeted with derision by the British and with disapproval by the Dublin republican establishment. Exactly three years later the last British solider quit South Tipperary. What happened in between is a significant story – at that moment in time Britain seemed as invincible as the United States seems today. The efforts of disenfranchised people wielding a hodgepodge of muskets, mud bombs, and captured weapons seemed as hopeless in 1919 as similar efforts by Vietnamese peasants seemed in the Sixties or as the Palestinian resistance seems now.

The real story – told in Dan Breen and the IRA for the first time in the words of those who participated in it – is considerably more moving and more interesting than the myth. Breen operated in the middle of a group of noteworthy individuals who felt that it was ‘the decree of history’ that they would stand or fall together. This is their story too.

When I was tramping with my mother through the roads and boreens of Tipperary in the Eighties, speaking to Dan Breen’s contemporaries and working on a small book about him, Ireland was in many ways identical to the country that he fought in and for. That has all changed now. The events of ninety years ago seem terribly remote. Few Irish people now know what a haggard is or what real hunger feels like. Oro Se Do Bheatha Bhaile, the song which the Third Tipperary Brigade sang as they marched through Tipperary’s Galtee Mountains, is today best known as a track on a Sinead O’Connor album. Many of the principles and aspirations which those people fought for seem neither here nor there. This makes the job of explaining what happened, whom it happened to, and why it happened at all, crucial.

Dan

Breen and the IRA is published in paperback at

€12.99