Metered

to Death: How a Water Experiment Caused Riots and

a Cholera Epidemic

Free water, he said, "gives the

impression that water is free, service is free

and you can use water as much as you want.By

Jacques Pauw

JOHANNESBURG, South Africa, February

5, 2003 — Every morning, as the sun rises

over the Indian Ocean and paints the sky a

brilliant yellow, David Radebe crosses the N2

freeway into another world.

Winding like a black snake

through green sugar cane fields and over rolling

hills, the freeway  divides

two very different communities along

KwaZulu-Natal's spectacular Dolphin

Coast. divides

two very different communities along

KwaZulu-Natal's spectacular Dolphin

Coast.

Thirty miles (50

kilometers) north of the harbor city of Durban,

the turnoff to the right leads to the resort

towns of Ballito Bay, Salt Rock and Tinley Manor,

where holiday homes of the upwardly mobile and

absentee landlords perch on rocky cliffs

overlooking brilliant white beaches. Radebe comes

here to look for work.

On the other side of the

freeway, heading toward the interior and

scattered between sugar cane estates, lie the

houses and dwellings of small ethnic Indian

communities and three black township settlements

that are home to about 12,000 people. This is

Nkobongo, where Radebe lives.

Rows of new government

housing line the tidy township streets. Roads and

curbs are well maintained. Electrical cables

crisscross the landscape above the tin roofs, and

township kids, dressed neatly in blue uniforms,

make their way to "Indian schools" that

now have been integrated.

But the air of progress

and order belies a quiet desperation. Eighty

percent of township residents live in dire

poverty, well below the minimum living standard

of R800 ($80) per household a month. The mobile

clinic that serves the townships reports an

alarming increase in cases of HIV/AIDS,

tuberculosis and malnourished children. Six in 10

residents say their children went hungry in the

last year.

Their biggest problem,

however, is water. Not because of a shortage, but

because they can't afford it.

It was in this stricken

community in 1999 that South Africa initiated one

of five water privatization programs as part of a

government policy aimed at making people pay for

the full cost of having running water in their

homes. The South Africans call it "total

cost recovery."

Unlike many countries,

where residents pay only a fraction of the total

cost of having running water in their homes, the

idea behind "total cost recovery"

— the brainchild of private water companies

and World Bank economists — is

that ending subsidies will help finance improved

waterworks and build the country's economy.

Free water "is not so

good an idea," Yves Picaud, managing

director of Vivendi

Water in South Africa, said in an interview with ICIJ. "It is

better to ask people to pay very little, but to

pay something." Free water, he said,

"gives the impression that water is free,

service is free and you can use water as much as

you want."

But in practice, total

cost recovery may have caused more misery than

development. In poor areas where privatization

has been implemented, millions of people have

been cut off because they cannot afford to pay

water bills that often make up 30 percent of

their incomes.

As many as 10 million  South Africans have had

their water cut off for various periods of time

since 1994, according to a 2002 national survey

by the Municipal Services Project, a

university-based research center with offices in

South Africa and Canada. Two million people have

been evicted from their homes for not paying

utility bills. Many poor families pay up to 40

percent of their monthly income for water and

electricity. South Africans have had

their water cut off for various periods of time

since 1994, according to a 2002 national survey

by the Municipal Services Project, a

university-based research center with offices in

South Africa and Canada. Two million people have

been evicted from their homes for not paying

utility bills. Many poor families pay up to 40

percent of their monthly income for water and

electricity.

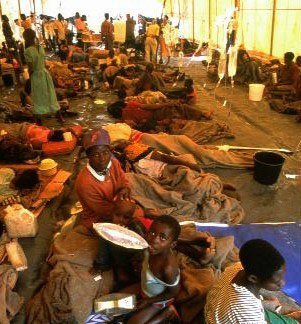

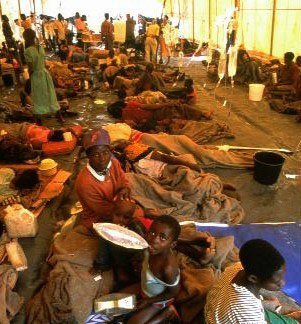

The water cutoffs have

forced thousands of poor people to seek water

from polluted rivers and lakes and led to South

Africa's worst outbreak of cholera, in which

thousands of people were sickened and hundreds

died. In the end, the government spent millions

of dollars to control the spread of the disease

and to truck clean water to the stricken areas.

"The cost recovery

program sounds good, but...it forced people to go

back to the original sources of water, polluted

streams and rivers and the like," said David

Hemson of South Africa's Human

Sciences Research Council, Africa's largest

and most-respected social science research

organization.

"That was the direct

cause of the cholera epidemic," Hemson said.

"There is no doubt about that." [Listen

to David Hemson]

"People are saying: I

have to choose between water and food — or

between electricity and sending my child to

school," said Canadian researcher David

McDonald. When it comes to cost recovery,

McDonald observed, "Nobody really ever

bothered to find out if people could afford these

services. And, as it turns out, people

can't."

Soaking the poor

In South Africa, total

cost recovery has been implemented in different

ways. Some local governments have privatized

public utilities by awarding water concessions to

foreign companies. Others have transformed their

utilities into profit-driven, publicly owned

enterprises.

In Nkobongo, where David

Radebe lives, the French water company Saur won a

30-year concession in 1999 to provide water and

purification services to the area's diverse

population of 40,000. Saur formed a local company

in consortium with four South African companies,

called Siza Water Company. Saur was the majority

shareholder, while the majority black South

African companies shared the rest.

Water that once was free

for the poor suddenly carried a price tag.

Initially, families such as Radebe's could afford

it. Pleased to have cool, fresh running water in

his new home for the first time in his life,

Radebe gladly paid the connection fee and his

first water bill — totaling 63.58 Rand

($6.40) — a copy of which he retains as a

keepsake.

But in 2001, Radebe lost

his job as a gardener at a construction company.

School fees, food costs and rising water and

power rates quickly drove the family into debt.

The household's electricity was cut off, and the

water stopped flowing. Radebe tried to install a

pipe to bypass his water meter but was arrested

and released on a warning. He had to beg the

school headmaster to reschedule the kids' school

fees. With no water, his vegetable patch dried

out and the electric stove — of no use since

the electricity had been cut — was

repossessed.

Radebe told city officials

he would never be able to pay. So they removed

his water meter altogether. Many of his neighbors

and friends also have been cut off. Ninety

percent of township residents now access water

from sources other than the Siza Water Company,

according to Hemson.

Facing mounting losses,

Siza Water Company did what most private and

public water utilities are doing. It raised water

rates — by between 98 percent and 140

percent since the inception of the concession

nearly four years ago.

Other, more inventive

tactics are being employed across the country.

Many townships have put

meters on communal taps. To access them,

residents must buy a prepaid water card, which

works like a phone card. The customer slips the

card into a meter and takes water from an

activated tap. The water stops when the card is

removed. When the card runs out, the customer has

to buy another. Trouble is, people like Radebe

can not afford $4.02 for a prepaid water card.

The prepaid meters are

"the most insidious device," said

McDonald, who co-directs the Municipal Services

Project, a research center based at University of

the Witwatersrand in South Africa and at Queens

University in Kingston, Ontario. "People

won't buy what they need — they'll buy what

they can afford. So people are simply cutting

themselves off rather than having the state come

in and do it."

Some of the metered

communal taps have been vandalized. Others just

don't work; they eat the water cards so that

customers not only lose their money, they lose

any chance for water.

Another tactic of water

control involves a simple disc with two tiny

holes, called "the trickler."  When people

miss a certain number of payments, the water

company inserts a disc into a valve, causing

water to trickle through to their pipes at

greatly reduced pressure. Residents can still get

a minimum amount of water — but only once or

twice a day. When people

miss a certain number of payments, the water

company inserts a disc into a valve, causing

water to trickle through to their pipes at

greatly reduced pressure. Residents can still get

a minimum amount of water — but only once or

twice a day.

Although Section 27 of the

South African Constitution guarantees citizens

access to sufficient food and water, families

like Radebe's have neither.

Instead, families

desperate for water in Nkobongo turn to the

nearby Mhlali River and other streams. Radebe

said he borrows drinking water from neighbors

when he can, but at times he has had to send his

kids to the river with plastic buckets to fetch

wash water.

The trouble is,

KwaZulu-Natal's natural water resources can be

deadly.

19th century epidemic, 21st

century economics

There was a time, said

Wilson Xaba, when the taps in the Ngwelezane

township just ran and ran. The water was clean

and free.

Ngwelezane is a two-hour

drive north of Radebe's township of Nkobongo in

the former homeland of KwaZulu. Of a population

of 1.5 million people, 79 percent do not have

access to clean water, according to Edward Cottle

of the Rural Development Services Network, a

private group that conducts research on social

issues.

Xaba leads a community

group called Shona Khona, which means "Go

There." It was started in response to the

community's dissatisfaction with increasing

service cutoffs by the municipality's

"commercialized" waterworks.

In 1982, KwaZulu suffered

a major outbreak of cholera. More than 12,000

cases were reported, and 24 people died. As part

of a relief program, nine communal taps were

erected by the apartheid government on the border

of Ngwelezane.

It was a historic

milestone for Ngwelezane. For the first time,

residents were able to access purified water.

According to Xaba, some residents made personal

connections to these taps and had running water

in their houses. For the next 17 years, the

community had free water.

Until 1998, the

municipality covered all costs of water from the

nine communal taps. But then the town council

introduced measures for more rigorous financial

management.

Residents were required to

pay a flat monthly rate of $4.50 for water and

electricity. At the end of 1998, the nine

communal taps were converted to prepaid meters.

To access water, residents had to pay a

connection fee of $5. Only 700 households could

afford the registration fee. Two-thousand

families remained unconnected.

"They came to us and

said we are wasting water," Xaba recalled.

"We were not consulted, they just told us.

For those houses with taps, they put meters in.

Then they put the prepaid meters in. We said 'no'

and then they cut our water. They said the water

belonged to the municipality. They used a phrase,

'No money, no water.'"

In August 2000, at least

four of the meters stopped working. "We

could not get water from anywhere. Nobody

explained anything. It took three weeks before

the meters were working again. The boreholes were

dry. We had no choice but to get water from the

rivers."

A survey by the Municipal

Services Project found that 11 percent of

Ngwelezane's residents said they got water from

the river as a result of the cutoff.

They started using ponds

and streams contaminated with cholera bacteria,

and the disease spread like wildfire. The

Ngwelezane/Empangeni municipality, which includes

the mostly white town of Empangeni, had $10

million in reserves that could have been used to

address the crisis, according to Edward Cottle

and David Hemson. But the municipal government

remained "impassive" in the wake of the

outbreak, Cottle said.

"There had been no

attempt to subsidize the extension of services to

poor communities," Cottle told ICIJ.

"The municipality rather sought to impose

prepaid water meters on the existing free water

supply and to subsidize industry through the

introduction of tax breaks and incentives."

The first cholera case in

Ngwelezane was reported in August 2000. Within

four months there  were

thousands of cases of the disease, which spreads

through food or water contaminated with cholera.

The causes of cholera have been understood since

the mid 19th century. were

thousands of cases of the disease, which spreads

through food or water contaminated with cholera.

The causes of cholera have been understood since

the mid 19th century.

The disease ultimately

spread to the Eastern Cape and then to the

capital, Johannesburg, becoming the largest

cholera outbreak in South African history before

it ended in early 2002.

According to government

figures, about 120,000 people were infected and

265 were killed. Hemson, who was sent by the

government to investigate the outbreak, disputed

the official figures and said more than 250,000

people were infected and just under 300 people

died.

Hemson said he discovered

that the municipal government had put locks on

people's taps, forcing them to take water from

the lake and river. "That spread this

cholera epidemic throughout the entire

community," he said.

The local council

eventually reacted by removing the prepaid meters

from communal taps and charging people a flat

rate of $2 to $2.50 per month for water. The

South African government gave KwaZulu-Natal $2.5

million in emergency funds to fight cholera in

the province. It also trucked water into the

affected areas at a cost of $45,000 per month.

"It is hard to fathom

how a democratic government, which prides itself

with promoting seemingly progressive water

legislation, could experience one of the biggest

outbreaks of cholera," Cottle said.

Unless the government gets

rid of its policy of cost recovery, "cholera

will continue to haunt South Africa for a long

time to come," he said.

And it will be costly. As

a result of trying to recoup its water costs, the

state is now paying "tens if not hundreds of

times more dealing with the health crisis,'' said

David McDonald of the Municipal Services Project.

Despite best intentions, the ANC blunders

Ronnie Kasrils got the

first hint that his government's cost recovery

policy was not working in 1999 during a visit to

a village in the former homeland of Transkei.

Kasrils, once a committed communist and soldier

in the African National Congress' armed wing, had

just become the minister of Water Affairs and

Forestry.

His department was

coordinating a project in the village of

Lutschenko in which each resident was

contributing 10R ($1) a month to receive basic

water service. While touring the village,

according to press reports at the time, he came

upon a woman digging in a riverbed.

"You don't have to do

this anymore — we have this project

now."

"I have to," she

replied. "I haven't got 10 Rand."

In February 2000, Kasrils

issued a new policy, giving six cubic meters

(1500 gallons) per month of free water to every

household in the country. But he failed to

provide rules to implement the policy.

By the end of 2002, 57

percent of all South Africans were getting the

free water, but fewer than a third of them were

poor. The remainder didn't need free water,

according to Kasril's department. And millions of

poor people still did not have the clean water

they needed.

The ruling African

National Congress makes impressive claims for its

record on water delivery. When it took power in

1994, 13 million South Africans did not have

access to clean drinking water. By February 2002,

the government said, it had reduced that number

to 6 million. Kasrils has promised "basic

supplies" of water and electricity for all

by 2008. [Listen

to the government's water promotion]

But the ANC's progress

report seems exaggerated. According to Cosatu,

South Africa's biggest trade union, 98 percent of

whites, but only 27 percent of blacks, had access

to clean water in their homes in March 2001. In

rural areas, only 2 percent of blacks had indoor

plumbing.

Despite South Africa's

rating by the United Nations Development Index as

a middle-to-upper-income country, one child in

every 22 dies before reaching the age of 1.

Diarrhea is a frequent cause of these deaths and

often is directly attributable to poor water and

sanitation. In many ways, South Africa still

remains two countries. The 13 percent white

minority is 18th on the Human

Development Index, equal to New Zealand. The

dominant black majority is 118, in line with

Bolivia.

Of all the countries in

the world, in 2001, only Guatemala had a wider

gap between rich and poor than the one that

exists in South Africa.

The World Bank takes credit

According to a 1999 World

Bank strategy report, the bank played an

important role in charting South Africa's

privatization strategy.

It used South Africa as a

sort of test laboratory to "pilot our

evolving role as a 'knowledge bank,'" the

report stated.

"The Bank has

provided technical assistance and policy advice

in virtually all sectors of the economy,"

Pamela Cox, World Bank director for South Africa,

wrote in the introduction to "South Africa

Country Assistance Strategy," a bank report.

The report stated that the Bank's International

Financial Corporation has played an "active

role in the further development of infrastructure

in South Africa and promote the increased

participation of the private sector in this

area."

It goes on to say that the

bank's primary objective in influencing South

African policies was to "help reduce the

apartheid legacy of poverty and inequality."

Unfortunately, it didn't turn out that way.

The bank sent its own

experts and brought in others to help South

Africa fashion a new economic policy that

involved decentralizing power partially through

privatizing utilities.

Patrick Bond, a professor

at the University of the Witwatersrand in

Johannesburg who has written extensively on water

privatization and the World Bank, told ICIJ that

the Bank sent what he called "reconnaissance

missions" in the 1990s to prepare the new

ANC government for privatization and

cost-recovery.

By the time the ANC took

over, World Bank advice was explicitly biased

toward privatization.

By November 1994, Bank

staff, led by the deputy resident representative,

Junaid Ahmed, had drafted the main sections of

South Africa's "Urban Infrastructure

Investment Framework." A final draft was

issued four months later under the auspices of

the Reconstruction and Development Ministry in

the office of President Nelson Mandela. The

framework provided for communal taps and for pit

latrines in areas where households earned less

than $80 a month, Bond said.

In October 1995, the World

Bank's main water expert on Lesotho and South

Africa, John Roome, advised then-Minister of

Water Affairs Kader Asmal to make several policy

changes. These included introducing a

"credible threat of cutting service" to

non-paying consumers.

In 1996, total cost

recovery became an official policy of the

government when it adopted its fiscally

conservative Growth, Employment and

Redistribution macro-economic policy, known as

GEAR. The central features of the policy are a

reduced role for the state, fiscal restraint and

the promotion of privatization.

Mike Muller,

director-general of the Department of Water

Affairs and Forestry, acknowledged the bank's

contribution but added: "The policy for cost

recovery has been in place long before the World

Bank was allowed to come here. And it's an

absolutely sensible way of running a water system

and the way most water systems are run in the

world."

Bond disagrees. "Much

of cost recovery to date in South Africa has been

driven by a blind ideological faith in

neo-liberalism," he told ICIJ. "There

has been no effort to explore alternatives."

Call me a Thatcherite

After taking office as

president in May 1994, Nelson Mandela proclaimed,

with a nod to Britain's proponent of

privatization, former Prime Minister Margaret

Thatcher, "Privatization is the fundamental

policy of our government. Call me a Thatcherite,

if you will."

Thabo Mbeki, who at the

time was Mandela's deputy president and succeeded

him in 1999, agreed with that position.

Municipalities have used

harsh tactics to enforce total cost recovery. In

certain towns in the Eastern Cape — the

traditional heartland of the ANC —

municipalities resorted to "apartheid

style" tactics to force people to pay. In

Stutterheim, streetlights were switched off to

"punish" non-payers. In Queenstown,

special debt collectors and private security

firms were appointed to collect arrears and cut

off water of errant residents. In Fort Beaufort,

local council officials refused to collect

sewerage buckets in so-called

"squatter" camps – where the

poorest of the poor live in tiny tin shacks.

Township protests broke

out around the country, with people demanding an

end to prepaid electricity meters and water

cutoffs. The demonstrations turned violent in

some areas, as protesters clashed with the

police.

"People are very,

very angry," McDonald, of the Municipal

Services Project, said. "We're starting to

see a ground swell of opposition."

The project, surveying the

impact of cost recovery on the poor, found that

more than a third of the 2,530 respondents

interviewed in July 2001 said they could

"not afford to pay for these services no

matter how hard they try" or that they could

pay only if they "cut back on other

essential goods like food and clothing."

In March 2000, one month

after Kasrils promised free water, the World Bank

released its "Sourcebook on Community Driven

Development in the Africa Region — Community

Action Programs."

Despite the hardships

already evident from total cost recovery

policies, the bank's report advised:

"Promote increased capital cost recovery

from users. An up front cash contribution based

on their willingness-to-pay is required from

users to demonstrate demand and develop community

capacity to administer funds and tariffs. Ensure

hundred percent recovery of operation and

maintenance costs."

McDonald said officials

disregarded the reality on the ground.

According to his research,

only 50 percent of households are capable of

paying a "reasonable fee" for services

such as water and electricity. Seventeen percent

of households can pay for services only if they

cut down on essentials, such as food and

clothing. Eighteen percent said they cannot pay

at all.

"Ability to pay is at

the root of the payment crisis, not a culture of

non-payment. You cannot squeeze blood from a

stone," McDonald said.

Menahem Libhaber, the

World Bank's senior water and sanitation engineer

in Latin America, told ICIJ there are thresholds

beyond which people simply cannot pay.

"Look, we can raise

the tariffs only by a socially acceptable amount

— 3 to 4 percent of income — if you get

to more than that, they will not pay,"

Libhaber said. "The World Health

Organization suggested you could go to 7 percent,

but to me just 5 percent. South Africa is paying

too much."

A countrywide study

released in December 2002 by the Department of

Local Government shows that many municipalities

are charging unaffordable and unreasonably high

service rates and people simply can't afford to

pay them.

South Africa's 300 local

councils are owed $670 million in outstanding

water payments, the study said.

The French connection

While privatization was a

post-apartheid policy, one French company already

had established deep roots in the country.

Lyonnaise des Eaux, now Suez,

was the first water multinational to create a

presence in South Africa — and it didn't

wait for the coming of democracy in 1994.

Ten years earlier, at the

height of apartheid, French foreign trade advisor

Henry Castelnau and two advisors to Lyonnaise des

Eaux's chairman, Jérôme Monod, arrived in South

Africa for talks with the government and local

authorities.

Through its wholly owned

subsidiary of Lyonnaise Water Southern Africa,

Suez bought interests in South Africa's largest

construction company and a pipe manufacturer in

the early 1990s. It then placed all of its South

African interests under Water and Sanitation

Services South Africa, a wholly owned subsidiary.

By 1995 the new firm,

known as WSSA, had management contracts in three

Eastern Cape towns: Queenstown, Stutterheim and

Fort Beaufort.

To drum up business, the

company used what Witwatersrand University

political scientist Greg Ruiters calls a

"panic strategy." Ruiters has

extensively researched the concession for the

Municipal Services Project.

WSSA officials met with

Fort Beaufort council members before the 1994

democratic elections and warned them that the

post-apartheid era was going to bring about

"demanding consumers, a payment crisis and

militant unions." The company claimed it

could help the three local councils solve these

pending problems, as well as provide substantial

savings and a world-class service. The Suez

subsidiary said consumption would rise and

consumers would start paying as they became more

aware of the "value" of water.

A secrecy clause was

written into the contracts preventing any member

of the public from seeing them without the

explicit approval of Suez, according to union

officials and Ruiters.

By 1996, the WSSA could

boast in its annual report: "Whilst these

are early days in winning their acceptance, we

now have the support of the government. We helped

draw guidelines of private sector management of

water and sanitation services and are now helping

with a regulatory framework."

But Ruiters said water

privatization in the three towns proved to be

disastrous. His research showed that water

tariffs increased up to 300 percent between 1994

and 1999. The municipalities did not derive a

cent of profit from its water revenue; all

increases went to paying off WSSA charges.

According to Ruiters, Fort

Beaufort paid $40,000 a month to the company.

By 1996, a typical

township household was paying up to 30 percent of

its income for water, sewerage and electricity.

Average income in the area at the time was less

than $60 per month, with more than 50 percent

unemployed.

The majority of township

residents couldn't pay their bills and were dealt

with ruthlessly. Queenstown appointed special

debt collectors and introduced a re-instatement

fee that was almost twice the average township

income.

The assistant treasurer

for Fort Beaufort, now called Nkonkobe, said in

his 2000 municipal report: "The majority of

debtors against whom action was taken are

pensioners or unemployed."

By the late 1990s,

old-style, anti-apartheid resistance tactics were

reemerging in the communities, with

stone-throwing and violent confrontations between

local authorities and angry communities,

protesting the electricity and water cutoffs.

Ruiters said the WSSA

showed "remarkable tenacity" in

clinging to its three contracts in the eastern

Cape. The company said in a 2000 monthly report:

"Based on our experience, we know that

revenue can be gathered humanely and

fairly."

But something had to give.

By 2000, Fort Beaufort municipality no longer

could pay the management fees to WSSA, and in

December 2001 it persuaded a High Court judge to

cancel its contract with the company. WSSA was

given two weeks to vacate the municipal offices

that they were occupying.

War by water pressure

In Nelspruit, a three-hour

drive east of Johannesburg, the water providers

and the water drinkers have had quite enough of

each other.

Henry Nkuna, for one, is

threatening war.

Nkuna was once a combatant

in the Azanian People's Liberation Army, the

armed wing of the Pan Africanist Congress, which

continues to be a leftist political party

favoring land redistribution and black

empowerment. The armed Pan Africanists gained

notoriety during the apartheid struggle for

masterminding attacks on whites in churches, bars

and on farms.

Now, Nkuna is declaring

his readiness to respond to new water policies

with violence. "If you dare to do cost

recovery in the townships, it will spark a

fire," Nkuna warned in a November 2002

interview. "It will be something you will

regret forever."

Nkuna's new enemy is the

Greater Nelspruit Utility Company (GNUC), a

consortium of the British water company Biwater

and a local black empowerment company, Sivukile

Holdings, which has a 30-year concession to

provide water and sanitation services to a

population of 240,000.

Brian Sims, GNUC's

managing director and head of Biwater in South

Africa, is a veteran water man. He has worked all

over the world: New Zealand, Australia, the

Philippines. "Name it, I've been

there."

"Never in my life

have I seen such a culture of non-payment than

here in Nelspruit," Sims said in disgust.

"People simply don't pay. We are suffering

massive losses."

In the summer of 2002,

GNUC instructed its lawyers to proceed with legal

action against 796 households in Nelspruit

that were more than $300 in arrears on their

water accounts.

"Letters of demand

have been sent out. This is the beginning of a

process to break the culture of non-payment in

the townships," GNUC commercial manager

Harold Moeng said in a November 2002 interview.

Nkuna and his

Anti-Privatization Forum are fighting to force

the municipality — now called Mbombela

— to cancel the GNUC contract and introduce

a flat rate of $3 a month for all municipal

services in the municipality and its surrounding

townships and villages.

"If it's necessary,

we'll use violence," he warned. "If

they [GNUC] come into the township to cut our

water supplies or take our goods, we'll vandalize

their cars and beat up their workers."

The threat of violence is

the latest in a series of obstacles and setbacks

for the concession, which has seen youths

marching on councilors' houses in the townships,

the destruction of water meters, illegal water

connections and one of the highest rates of

non-payment in the country.

| Nelspruit Like the rest of

South Africa, Nelspruit

is really two cities. Old Nelspruit is

white and prosperous with average annual

incomes of $13,000. The surrounding

townships are poor. About 60 percent of

households have an income of $100 per

month or less.

When GNUC took

over in 1999, residents in the old town

enjoyed First World living conditions:

wide and well-maintained tree-lined

streets, libraries, parks, superior

medical facilities, good schools and a

high-level of municipal services. By

comparison, non-existent or low-level

basic services, dirt roads and inferior

schools and medical facilities

characterized the townships.

The municipality

privatized its water operation because it

needed $38 million to bring water and

sewage networks to the townships. Since

then, GNUC said it has laid 90 kilometers

(55 miles) of new water pipelines and 17

kilometers (10 miles) of new sewage

pipelines. It has installed 7,240 new

water meters and made 5,000 new water

connections.

But Sims

acknowledge in an interview that Biwater

is at a "crossroad" in its

operations in South Africa. Sims said

Biwater can no longer afford to implement

its full obligations under the water

concession, and the company has suspended

all capital expenditure programs. Even

with the suspension, water rates

increased in 2002 by 18 percent.

Sims blamed the

problems on the "culture of

non-payment" in the township, fueled

by trade unions and their allies like the

Pan Africanist Congress.

It costs the

consortium $111,000 every month to supply

clean water to Kanyamazane township,

which is part of Nelspruit, Sims said,

but the consortium receives only $5,584

in revenue. Only about 20 percent of

residents pay their bills. They

collectively owe the utility $1.8 million

in unpaid water bills.

"There is

only one solution: we have to get people

to pay," Sims said, adding that even

those township consumers who can afford

to pay for water don't.

But a journey into

the poor areas of Nelspruit tells a

different story. It becomes clear that

most people, at least, don't pay because

they cannot afford to pay.

People were used

to a flat rate of about $7.50 for all

services before privatization, said Sam

Sambo of the South African Municipal

Workers Union, a trade union that stands

at the forefront of the

anti-privatization campaign in South

Africa.

Now, they get

individual water bills of up to $20.

"It's beyond their ability to pay

and that's why only one out of every five

residents pays their bills," Sambo

said.

The Pan Africanist

Congress initiated a campaign in 2001

called "Operation Vulamanzi,"

or Operation Open Water, to reconnect

water to all residents who had been cut

off for not paying their bills. Even so,

"debtors" receive their water

through the so-called "trickler

system" in which GNUC installs a

disc-like device with two tiny holes that

allows water only to dribble into the

pipes.

"People can

still access their free [6 cubic meters]

of water every month. In fact, they can

get even more," said Harold Moeng,

GNUC's commercial manager.

But the trickler

makes life very unpleasant for those who

can't pay. Call it war by water pressure.

"People often

have to get up at 3 a.m. to get water

before they go to work and then wait

again for the pressure to build up,"

Sambo said.

He said GNUC's

attempt at total cost recovery is war on

the poor. "We will resist it with

every possible means we have."

Nkuna rattles his

saber: "If they continue on this

path, we will start with meetings and

rallies and rolling mass action. Things

can turn ugly. We will meet violence with

violence."

The water miracle?

Sitting in his

office outside Johannesburg Development

Bank building, James Leigland – the

man who brokered the privatization deal

in Nelspruit – is convinced that the

process has ground to a halt.

"Further

privatization of water? It's not going to

happen in the near future. There will be

no new Nelspruits or Dolphin Coasts.

There is too much of a downside," he

said.

Leigland

represents the Municipal Infrastructure

Investment Unit, which the government

created in 1997 to "encourage and

optimize private sector investments in

local authority services." He

praised the local achievements of Biwater

and GNUC as numerous and said that

bringing water to the poor in Nelspruit

has been very successful. "This

would not have been possible without

privatization. We couldn't have done it

without Biwater."

But he

acknowledged the concession is "very

fragile."

"Private

companies were anxious to get a foothold

in the country," Leigland explained.

"They are still very eager, and I

don't think they have been totally

discouraged. But there is a lot of

mistrust towards them."

Indeed, the

foreign multinationals appear to be

reassessing their position in southern

Africa.

Saur has withdrawn

from Mozambique and Zimbabwe. Suez has

not appealed the cancellation of its

Nkonkobe contract in the Eastern Cape.

Biwater says it is committed to

Nelspruit, but is not seeking any further

concessions. Thames

Water has no presence in the country.

Vivendi's one executive seems wary of the

situation.

"To be very

honest, the municipal market is not

ready," said Picaud, the managing

director of Vivendi Water in South

Africa.

South African researcher David Hemson

next to a destroyed water meter. (Photo: Bob

Carty)

|

|

debate formed in Sweden over

plans to dam the country's remaining free-flowing rivers

for hydropower. He says that proponents of the project

told him not to worry about the environmental impact

because most rivers elsewhere in the world remained

untouched.

debate formed in Sweden over

plans to dam the country's remaining free-flowing rivers

for hydropower. He says that proponents of the project

told him not to worry about the environmental impact

because most rivers elsewhere in the world remained

untouched. divides

two very different communities along

KwaZulu-Natal's spectacular

divides

two very different communities along

KwaZulu-Natal's spectacular  South Africans have had

their water cut off for various periods of time

since 1994, according to a 2002 national survey

by the Municipal Services Project, a

university-based research center with offices in

South Africa and Canada. Two million people have

been evicted from their homes for not paying

utility bills. Many poor families pay up to 40

percent of their monthly income for water and

electricity.

South Africans have had

their water cut off for various periods of time

since 1994, according to a 2002 national survey

by the Municipal Services Project, a

university-based research center with offices in

South Africa and Canada. Two million people have

been evicted from their homes for not paying

utility bills. Many poor families pay up to 40

percent of their monthly income for water and

electricity.

When people

miss a certain number of payments, the water

company inserts a disc into a valve, causing

water to trickle through to their pipes at

greatly reduced pressure. Residents can still get

a minimum amount of water — but only once or

twice a day.

When people

miss a certain number of payments, the water

company inserts a disc into a valve, causing

water to trickle through to their pipes at

greatly reduced pressure. Residents can still get

a minimum amount of water — but only once or

twice a day.  were

thousands of cases of the disease, which spreads

through food or water contaminated with cholera.

The causes of cholera have been understood since

the mid 19th century.

were

thousands of cases of the disease, which spreads

through food or water contaminated with cholera.

The causes of cholera have been understood since

the mid 19th century.