THE HANDSTAND

MAY 2005

Fire and rage in the

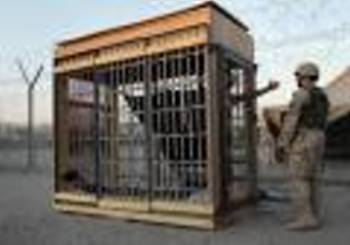

shadow of Abu Ghraib

Rory

Carroll in Baghdad

Sunday April 10, 2005

The Observer Excerpt.

An orange sun set over the city, casting just enough

light to finish the kickabout, when the players heard the

unmistakable sound of rockets whooshing overhead.

Seconds later the missiles slammed into Abu Ghraib, the jail adjoining their football pitch. Explosions resounded across the complex and more rockets were launched. The Americans fired back.

The 25 children and seven adults sprinted to a wall enclosing the school grounds and huddled together, waiting for the storm to pass. But the attack intensified and bullets peppered closer so the group scrambled into a communal toilet. They cowered in darkness as hits on their shelter showered dust and masonry fragments. Some of the children started to sob, vomit and soil themselves.

'We put our hands in the children's mouths to stop them crying. It was the most difficult time of my life,' said Abu Mohammad, 38.

For 12 hours the group crouched in the three-square-metres space, murmuring prayers as car bombs detonated outside, until dawn broke and they emerged, waving a white T-shirt, to a scene of devastation. The attack on Abu Ghraib, a symbolic target since last year's inmate abuse scandal, underlined a shift from hit-and-run ambushes to large-scale assaults.

To tackle the sprawling complex 20 miles west of the capital, which doubles as a US base, they used almost every type of weapon in their armoury.

Only now have those caught in the crossfire given their version. It partly contradicts the US and al-Zarqawi statements by claiming there was chaos and panic on both sides and, in the aftermath, looting by US and Iraqi security forces.

Mohammad, one of the adults who sheltered in the toilet with the children, including his three-year-old son, lives in Khan Dhari, a district near the jail inhabited by working-class Arab Sunnis hostile to the occupation. As they do most Saturdays they met in the grounds of a primary school on the south-western side of the jail to play football. Guards in watchtowers would have seen that the group was mostly young children, said Mohammad.

When rockets landed around

them, guards returned fire wildly, apparently unconcerned

about civilian casualties. Even when searchlights 'turned

the place into day', US bullets continued hitting the

school despite the absence of rebels there, he said. At

some point the jail gates opened and Humvees roared out -

probably the rapid-response forces - only for a black

Opel packed with explosives to slip into the convoy and

blow up. 'It was a hell of fire,' said Mohammad, a tall,

wiry Islamic scholar, who said he saw charred Humvee

engines and a human hand and leg. From the toilet his

view was restricted, but the next day relatives and

neighbours filled in details. Two suicide bombers in

South Korean-made KIA vehicles rammed tanks. Another

bomber driving a pick-up truck got lost and knocked on

doors asking directions to the nearest US target. 'He was

a foreigner and asked why people were not coming out for

jihad.'

When rockets landed around

them, guards returned fire wildly, apparently unconcerned

about civilian casualties. Even when searchlights 'turned

the place into day', US bullets continued hitting the

school despite the absence of rebels there, he said. At

some point the jail gates opened and Humvees roared out -

probably the rapid-response forces - only for a black

Opel packed with explosives to slip into the convoy and

blow up. 'It was a hell of fire,' said Mohammad, a tall,

wiry Islamic scholar, who said he saw charred Humvee

engines and a human hand and leg. From the toilet his

view was restricted, but the next day relatives and

neighbours filled in details. Two suicide bombers in

South Korean-made KIA vehicles rammed tanks. Another

bomber driving a pick-up truck got lost and knocked on

doors asking directions to the nearest US target. 'He was

a foreigner and asked why people were not coming out for

jihad.'

By 5.45am the football players, thirsty, exhausted and terrified, heard the wail of a mosque's muezzin summoning people to prayer. They ventured out to be met by Iraqi soldiers who were astonished no one was hurt given the damage to their shelter. Suspicious, the soldiers demanded to see the football as proof of their story. It was found in a corner of the pitch.

Mohammad, who made no secret of his sympathy for the rebels, claimed that in the clampdown that followed Iraqi troops broke into dozens of shops and looted fruit, biscuits, soft drinks and electronic goods. US troops joined in, he said, with one soldier wresting a bag of mobile phones from an Iraqi and several others catching a goat and a sheep which were driven in a Humvee back to their base. There was no way of verifying the allegation.

Two

months after the election Iraq's parliament named a

President and Prime Minister last week, paving the way

for a new government which is expected to accelerate the

handover of security from coalition to Iraqi forces and

empower the majority Shia community. But tens of

thousands of militant Shias who gathered in Baghdad

yesterday demanded an immediate pullout, or at least a

timetable. 'No, no, to the occupiers,' they chanted,

waving effigies of George Bush and Tony Blair.

Fighting Torture with Art: The Paintings of Fernando Botero

By Mike Whitney

Al-Jazeerah, 14 April, 2005

The Columbian artist Fernando Botero has produced a

brilliant collection

of life-sized paintings depicting the horrors of Abu

Ghraib. The works show prisoners bound and gagged,

stacked on top of each other, and being beaten by

American soldiers. The paintings have a haunting,

frenzied feeling to them, like Pieter Bruegel’s

medieval “The Triumph of Death” (1562) where

the artist conjures up a scene of armies clashing while

wagon-loads of skulls are carried across an

apocalyptic-looking landscape.

Abu Ghraib is the entryway into that same world, faithfully reproduced in excruciating detail by George W. Bush. We’re fortunate to have men like Botero shine a light on the real machinery of Bush’s terror-apparatus. Already, 100,000 Iraqis have died in a gratuitous act of aggression, entire cities have been flattened and 17,000 Iraqis languish in overcrowded gulags waiting for an improbable turn-of-events. Botero captures the look of desperation on men’s faces when there is no expectation of justice. He confronts his audience with the bloody stanchions that support the new world order and the increasing number of innocent victims required to keep them upright. This isn’t the stuff you’ll see in the media, where America’s war crimes are concealed behind a heavy lacquer of flowery rhetoric and optimistic predictions. These pictures are the real deal, like the grinding violence and humiliation produced by a brutal occupation.

Let’s hear Bush offer a few choice words about God’s work in Falluja, where “combat-aged” males were barricaded in the town so they could be peppered with cluster bombs and napalm. Or, perhaps he can brighten his oratory with anecdotes about prisoners rotting away in his string of concentration camps that are now scattered across Iraq. This is what makes Botero’s work is so valuable; it strips away the pretense and shows the ghoulish face that operates behind the mask.

Picasso’s masterpiece “Guernica” has galvanized generations to the horrors of war. Botero’s paintings will undoubtedly have the same affect. His work shows in the plainest terms a world that has been knocked off its axis by Washington’s bloodlust. This is what the world looks like when the law has been jettisoned and men are subjected to the willfulness of megalomaniacs. Torture is never extraneous; it reflects the very heart of a regime. So it is with the Bush administration.

Botero’s paintings show us the violence that animates the Bush government and portends an increasingly uncertain future for us all.