|

|

| THE HANDSTAND | JANUARY 2004 |

| .They call

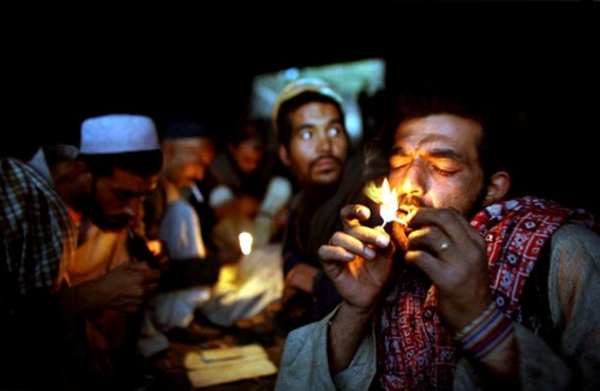

someone who takes drugs `sarut' [scratched]. “B., 24, returned from India a short time ago from a backpacking trip to Manali and Varansi. ‘Drug trafficking is not the issue,’ she says. ‘Drugs are not the issue - the issue is the sick Israeli society. The society of war. They have to understand that drugs are a substitute for something that young people don't get in this country.’ "’They call someone who takes drugs `sarut' [scratched]. Dorothy  Ha’aretz Friday Magazine December 20, 2003 Dozens of Israeli backpackers are under arrest at the moment in various places in the world on suspicion of drug trafficking. Most of them are ordinary 20-somethings seeking to get away from it all, but as far as the Interpoland local police are concerned, they are just the tip of the iceberg http://www.haaretz.com/hasen/spages/373564.html Hebrew: http://www.haaretz.co.il/hasite/pages/ShArtPE.jhtml?itemNo=372697 &contrassID=2&subContrassID=13&sbSubContrassID=0 By Vered Levy-Barzilai He (or she) is a backpacker in his mid-twenties, who grew up in a good socioeconomic environment, in an upper-middle-class family. He served in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), was discharged without any special problems, saved a little money and went off to see the world. Sometimes he completed his bachelor's degree first; sometimes he went on his journey before studying.He has no criminal record. He smoked grass and hashish while still in Israel, occasionally took Ecstasy at parties, maybe even tried LSD. During the course of his travels, he began to use much larger quantities of drugs. Most of the time he was surrounded by young Israelis like him, who, over time, developed an obsessive attitude toward drugs. Almost without noticing, drugs became a central component of his trip. He went to Full Moon parties. Lived in "laid back" youth hostels in Europe or in cheap guest houses in India, Thailand or South America. He looks innocent. He doesn't stand out. He's dressed in jeans and a T-shirt, or he may sport baggy sharwal pants. He's intelligent. Self-confident. Speaks good English and knows how to manage in almost any situation. Has initiative and daring. Often he has a combat background. Knows how to use weapons. Has a clear tendency to take risks. He is even willing to take a big risk in exchange for a chance to make a large, easy, quick profit. This is the profile of the "Israeli drug dealer" that was prepared by Interpol and the Israel Police and distributed among police forces the world over. It is based on the testimonies of many local drug dealers who were caught in various European countries as well as in Brazil, Peru, Uruguay, India, Thailand and other places. During the course of their interrogations, these dealers provided the profile of the young Israeli backpacker, and they are the ones who bestowed upon him the dubious title of the ideal drug runner . In the 1980s, only a few Israelis were arrested each year on suspicion of drug dealing. Most of them were people with a "criminal profile." In the 1990s, the number increased significantly. Since 2000, it has become a worldwide phenomenon whose dimensions are hard to ignore, and Israeli backpackers have become a significant factor in the international drug industry. The exact statistics are not known, but according to the Israel Police and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, at the moment dozens of Israelis are under arrest on suspicion of involvement in drug dealing. Many of them are young people who fit the profile presented in above perfectly: Young people who grew up in an ordinary environment, left Israel for an innocent trip, seeking adventure, and became involved in crime. With such an attractive personal profile, backed by the usual Israeli network of contacts, relationships built on trust and great mobility, it isn't hard to understand the affection of the big dealers for these Israeli backpackers. It's more difficult to understand how young people who grew up in a normal atmosphere turn into international criminals who are of interest to Interpol. `Steadily growing phenomenon' The answer apparently lies in the numbers. Commander Irit Buton, head of the Special Assignments Unit in the Intelligence Division of the national headquarters of the Israel Police, estimates that no more than 5 percent of drug smugglers are caught. The math is simple: If dozens are caught, many hundreds or even thousands are active. "Unfortunately, this is a steadily growing phenomenon," she says. "Police forces all over the world are aware of that. Therefore they assembled the profile of the backpacker. I have been at police facilities where people already consider Israeli backpackers a type of mafia." Buton is responsible for coordinating investigations of international criminal cases. An intercontinental police operation in which she participated led about two weeks ago to the exposure of a network of young Israelis suspected of drug dealing all over the world. The police waited for almost three years until they could get their hands on them. They suspect that the network included 14 young men and women, who were involved in dealing Ecstasy and cocaine. The network was headed by Assi Ben Mosh, who, together with his friend, escaped prisoner Ronen Attias, bought the drugs in Holland and distributed them all over the world, using Israeli drug runners. Police found 25 kilograms of cocaine and hundreds of thousands of Ecstasy pills in their luggage. The arrests were carried out in Peru, Brazil, New Zealand, Austria and Holland. Eight of those arrested are aged 20-plus, four are in their thirties, one is 20, one is 18. This group, says Buton, enjoyed a turnover of millions of dollars. She estimates that 10 of the 14 began as innocent backpackers who went for their big post-army trip. They were drawn to areas with lots of grass and Ecstasy. They joined people who used drugs daily, went over to harder drugs like LSD and cocaine, and became an integral part of the group of users and dealers . At a certain pointthey were tempted by large financial profit in exchange for performing an easy service - delivering a small amount of drugs from one country to another. The head of the group, an experienced drug dealer, sold the idea to them as being something that was not especially dangerous, with a negligible risk of complications. They were tempted, succeeded, weren't caught and were paid generously. Buton: "Young people like that, hanging around in a hostel in Europe or a guest house in India, have barely enough money to continue their trip. They don't feel comfortable calling home again and asking for money in order to buy drugs or food. For them, $1,000-$2,000 is a very attractive sum. Not to mention the huge sums offered by drug dealers for smuggling larger quantities. Then it reaches $10,000, and sometimes more. The sentences are heavy, varying between three to seven years of prison, but they feel they're on the top of the world, and can't think of a reason not to repeat the pattern again and again." Over time, they become daring, the amounts that are smuggled increase, the destinations change, the risks involved mount - and with them, of course, the expected profits. Until the backpackers themselves become drug dealers, who distribute commercial quantities all over the world. The young Israelis in Assi Ben Mosh's group don't completely suit the profile of the typical Israeli backpacker who becomes a drug dealer. Chief Superintendent Haim Eliyahu, head of the drug unit in the Intelligence Division at national police headquarters, distinguishes between those who link up with the underworld and the large drug networks, and become bona fide criminals - and amateur drug runners, whose profile we presented here. Today police investigators are interested in the small fry, too - those who are hanging around Indian guest houses or European hostels and doing their "internship." That's where the large dealers find them. Law officers want to engage in preventive police work, to locate them before they get into big trouble. "Last year they caught dozens of backpackers who smuggled drugs from place to place inside India. And we (the Israel Police) also caught dozens who smuggled drugs from India to Israel," says Eliyahu. "We're talking mainly about smuggled Indian hashish - charas - by backpackers aged 20-27, who return from their trip and carry the drug on their person, or those who have hidden it in various ways. Some were caught in Israel, some were caught in Europe." Where do they hide it? Eliyahu: "They have hiding places. For example, inside packages they send home to themselves by mail. They have a system. They flatten out the substance, which is like modeling clay, into thin slices. They put it into envelopes, books, toiletry bags, statues, clothing." So you're actually talking about kids who return from the trip and send themselves a small, personal amount of charas. "Excuse me, who said personal use and who said small quantities? Sometimes these are relatively small quantities, but often they are totally commercial quantities. I'm talking about people who sell; they have clients. And they are out-and-out drug traffickers. They aren't the classical criminals, and they usually don't deal in hard drugs. These are backpackers who saw how cheap charas is in India, and what a tremendous profit they can make from selling a certain amount in Israel, and couldn't resist the temptation. But they are drug smugglers. Abroad these differences certainly don't interest anyone. And even in Israel, in the courts, their spiritual `shanti' motives won't stand them in good stead and won't be considered extenuating circumstances. Drug smuggling is drug smuggling, and drug trafficking is drug trafficking. Moreover, many cases begin with `only smuggling a small quantity,' and turn into an entirely different story." How it begins What causes hundreds, and maybe thousands, of young Israeli backpackers from good homes to be drawn every year to the underworld, and to become international drug traffickers? What is the point at which a backpacker who smoked charas with the guys becomes a drug runner? Where is the line drawn, who are those who cross it, and why? In the hope of receiving answers to some of these questions, we went to Kfar Izun ("izun" is the Hebrew word for "balance") in Kibbutz Sdot Yam, which is managed by Omri Frish. This is a therapeutic rehabilitation village for backpackers damaged by drugs, who returned from their trip but didn't return to themselves. They suffer from psychotic incidents, anxiety and panic attacks, detachment from reality and other side effects, some reversible and some irreversible, which they brought home with them from their journey to discover the world which, as Eliyahu says, turned into a journey to discover drugs. Since they come from an upper-middle-class background - exactly as described in the Interpol profile - their parents send them to Kfar Izun, at a cost of about NIS 10,000 per month, instead of hospitalizing them in a psychiatric ward. At Kfar Izun they receive close personal psychological, physical,holistic and alternative treatments, which are meant to return them to a state of equilibrium. Along with the the statistic published this year by the Anti-Drug Authority - "90 percent of the backpackers use drugs" - Frish claims 90 percent success in curing these damaged young people. But they are still a negligible minority. Every year 50,000 backpackers set out from Israel (30,000 of whom reach India). Of them, about 2,000 return with some sort of psychological damage, and 600 are hospitalized in psychiatric wards and require long periods of treatment. The others wander around, lost, finding it difficult to function, but they deny or repress their condition; sometimes they are treated and sometimes they are even hospitalized. There are only 24 rooms at Kfar Izun - in other words, 24 patients at a time, and only the children of the top 10th percentile manage to get there. Frish, a social worker, a man with a vision, and the founder and director of the village, doesn't allow us to meet with the patients, only with the therapists and counselors. Discretion is essential here, and the good of the patients comes first. He is afraid that exposure to the media, even anonymous , may harm the patients. Therefore, only Frish, Nimrod - who is a former counselor at the village, and doesn't want us to mention his last name - Chen Ofer (the coordinator of the counselors) and Daniel Oved, a counselor at the village, participate in the conversation. The four are in agreement regarding the first stage: how it begins. Ofer: "You have to understand the background, the atmosphere, the entirely different existence. Everyone uses charas. Nobody even remembers that it's illegal. It's considered good and positive. On this basis, bringing a small quantity from Manali on the way to a party in Goa is the most natural thing in the world. Not a `crime' or anything. If a policeman were to come to such a backpacker and tell him `You're a drug trafficker,' he would fall down laughing. That's how it begins." There are differences of opinion among the four regarding the continuation of the process. Ofer thinks that the financial part is marginal. "It's totally a social thing. You bring merchandise, you're with it, you're cool. People come to you to buy. If you also have Ecstasy and some trips, you're even more respected. I know that guys who definitely don't need the money do it." Nimrod warns against whitewashing the business. In his opinion, money is definitely a central factor. "Think about a 20-something girl who went on a trip like this by herself. Her money has run out. She really wants to continue to travel. She has met many challenges, overcome many fears. To deliver a drug from one place to another in order to pay for the rest of the trip doesn't seem a big deal to her. Sometimes there's a point when one suddenly comes to one's senses, but in most cases there isn't and the law of averages talks - in most cases, it `works.'" What do you mean by "when one suddenly comes to one's senses"? Nimrod: "I want to emphasize that we're talking here from our personal experience, from our familiarity with the places and with former friends with whom we were together in India. This isn't empirical research, and we're not talking about present patients. I have a friend who wanted to bring charas , she wrapped it in plastic and put it into her vagina. Honestly. She passed through the first airport, got onto the plane, and in the middle of the flight understood what she was doing. She went to the bathroom on the plane, took it out, threw everything into the toilet and flushed. That's what I call coming to one's senses." Ofer: "It's hard to define motives. Each person brings who he is into the situation. There are cases of cynical exploitation. The dealers adopt young people who look like they have potential. They nurture them. Seduce them. I know of a case of a dealer in India who wanted to smuggle coke to Japan. But he didn't want to take a risk. Two young Israeli girls were caught in his net. What motivated them? In my opinion, the huge financial profit that awaited them. He convinced them that it's nothing. They took the stuff, and the three of them got on the flight together. At the entrance to Japan they were caught. He turned his back and continued on his way as though he had no connection to the issue, and flew on a connecting flight to Australia. They were arrested and sent to prison. The backpackers are not professionals , they don't know the codes, and they're enthusiastic. That's why, in most cases, they're the ones who'll pay the price." The Magical mystery tour One out of 10 The counselors and therapists at Kfar Izun estimate that one out of 10 back packers is involved at some level or other in drug smuggling. Ten percent! In other words, of 50,000 backpackers who go on a trip every year, about 5, 000 will, in their opinion, be involved in drug dealing. If we cross-check this statistic with the police statistics that mention dozens of dealers who are caught, and hundreds and maybe even thousands who are involved in drug dealing, we can reach the following conclusion: Several hundred, up to 1, 000, young people become real drug traffickers. Of the kind who smuggle commercial quantities of drugs between countries. The remaining thousands are small fry, the "rabbits" - the ones who deliver relatively small quantities of charas, Ecstasy and LSD within the country where they are staying, and sell them at parties and other large events. Daniel Oved: "I knew a young Israeli woman who became a serious dealer. A pretty, sweet girl from a good home. I had conversations with her. I tried to understand why it had happened to her. It really wasn't a matter of money for her. She was seeking warmth and love. Attention. She started to sell charas to the guys, and became a focus of attraction. She told me what a good feeling it gave her. Everyone always knew that she had stuff. There was action around her. She had a new feeling of power. "She began to use hard drugs, and to deal in them. She graduated to the big leagues. She started to smuggle drugs between countries. She's a sophisticated girl, and she wasn't caught. That's not surprising, because anyone who sees her will have a hard time connecting her appearance to this story. She became a heavy drug trafficker and wasn't caught. When I spoke with her a few months after she returned to Israel, she said: `Daniel, I had no idea what I was doing. It was like a film.' She pulled herself together. Didn't believe what she had come to. Only after it was all over did she understand what she had actually been doing. Who she had actually been." Frish says that anyone who is familiar with the world of the young people in India won't be surprised at the statistics. A backpacker in India who doesn't want to live like a dog, spends $8-9 daily, including board, food, trips and entrance to various places. One day his money runs out, and he needs only a few hundred more dollars in order to continue. In any case, he planned to travel to Goa. In any case, he planned to rent a Vespa. Someone comes and suggests that he only take a tiny package there, and he has the price of the rest of his trip. That's the whole story. Frish recently returned from a one-month stay in India, as part of a mission sent by the Prime Minister's Office and the Anti-Drug Authority. He met with hundreds of backpackers and held conversations with them. "The drug culture in India among Israelis is even greater and more profound than I had thought, and I'm familiar with the subject," he says. "One could say in general that almost the only thing that everyone (or almost everyone) does there is use drugs. There are processes here that affect each another. I assume that the worse, and the more pressured, the situation gets in Israel, in terms of security and economics, the greater their need is to run away and their tendency to become druggies. Some of it stems from well-known Israeli attitudes like, `It won't happen to me' and `It's nothing to me.' The person who said that told me that he had just taken four Ecstasies. He is a `graduate' of a prestigious combat unit. He has already seen and done everything. What's Ecstasy to him? Child's play. And let this be clear: We are talking about the best graduates of prestigious IDF units, and even medical students. Intelligent, spiritual, artistic, intellectuals. The best guys and girls there are." Did they tell you about the trafficking? Frisch: "Yes. They freely told me, `Here and there someone suggests that you deliver a kilo. Or a few thousand Ecstasies and LSD. So I did. Why not? Man, I got $1,000 clear.' It's very sad. In the end it's supply and demand. When there's such great demand, someone has to supply the goods. They're th ere in any case, they're moving around in it in any case, so the fact that they turn into fetchers and carriers seems entirely natural." Still in shock Haim Messing, the director general of the Israel Anti-Drug Authority, headed the mission that went to India last summer in order to estimate the extent of drug use among the backpackers. "Our consul general in India told me that our backpackers are sometimes exploited for delivering drugs in envelopes, in packages, under the camouflage of their backpacks and their gear," he says. "This happens within India, and from India [spreads] to the outside." Messing was still very surprised when he heard the assessments of the polic e and the staff of therapists and counselors from Kfar Izun. "It sounds exaggerated to me - the authority doesn't have such statistics. If they're correct, it's an earthquake. If there are such numbers, the government authorities, and we first of all, are obligated to get more deeply involved, to publish court decisions and punishments received by Israeli drug dealers, so others will see and be careful." Messings points out that the authority is constantly issuing brochures for backpackers, which include warnings, explanations of the severe sentences and the inhumane prison conditions in various countries for drug users and traffickers. Apparently, this is all in done vain. He returned from the trip very frustrated. "I saw innumerable young men and women who were drugged, phlegmatic, apathetic, who weren't interested in anything except drugs. Lying around like corpses in their rooms, not traveling, not curious, not wanting to learn, not connecting to people, nothing. You know what - there isn't even sex there. One would expect that in a place with such a concentration of young people there would be an exciting sexual atmosphere, wouldn't you? Nothing. They're really exhausted. It's terrible. It's very sad." What's the solution? Messing: "Information and education. What else can we do? We'll soon be opening our own branches there for first aid for those hurt by drugs, until they are brought to Israel. We'll intensify the information campaign and education in the schools, in the army, in the universities. There's no other solution. Now you have supplied us with a new front in the war - drug trafficking. We'll have to examine, together with the prime minister, the Foreign Ministry, with all the organizations, how to attack this issue in a proper and effective manner. It's a difficult and complex problem with no simple solutions." `Sick Israeli society' B., 24, returned from India a short time ago from a backpacking trip to Manali and Varansi. "Drug trafficking is not the issue," she says. "Drugs are not the issue - the issue is the sick Israeli society. The society of war. They have to understand that drugs are a substitute for something that young people don't get in this country. "They call someone who takes drugs `sarut' [scratched]. They think it's his illness. But they're wrong. His illness is something else. A month or two ago this young man was in the territories, and he saw a man or a child whom he killed. A month ago this young man entered the home of an Arab family at night, beat a child, a mother and took the father into detention. That's what `scratched' him. That's his emotional disturbance. Not the drugs. He t akes the drugs in order to try to forget the pictures that are with him all the time since then. I'm not saying that's true of everyone. But everyone has a strong need for escape. For liberation. .(Doctors have no medicines anymore. People are being murdered at random. It's so unsafe, and pure hell for these people. The Israeli media won't let the western media into the areas where the atrocities are taking place." From a friend's letter.Ed.jbraddell) "There are many possible explanations. But it all always comes back to the abnormal situation of our life here. In a society of war. Charas is a drug of love and freedom. There's nothing negative about it. And what is happening is India is an expression of the strong desire of young Israelis to escape from the insanity that has been forced on them. "The organizations involved in the war against drugs like to talk about the `corridor' that leads from grass to hard drugs. We're talking about an entirely different corridor, into which we were pushed at the age of 5 or 6. Be good children. Go to kindergarten, to school, to high school, to the army , to university. Get married. Have children. And what about our lives? And what about what we wanted? In this screwed up corridor, there's no personal guidance. There's no loving attitude. There's no freedom. Either you're on track, or you're a failure. It's a framework that suits some children. All the others: If they were lucky, their parents registered them for open, democratic schools. If not, they fall behind, are pushed out. They lose faith , stop studying. "I emerged from this system like that. They didn't see me. They didn't understand me. They didn't meet my needs. They didn't try to meet me halfway. They didn't offer me alternatives, a place where I could have expressed my unique talents. And from there, to the army - what is this?! To enter a world of war at the age of 18. So how do they want us to come out sane? How do they expect us to want to know, and to get something else from this world. Drugs enable many people at my age to experience a type of openness, love, warmth, and that's a really good means of communication. It's certainly better than the means of communication of the army and of the school system. "Some people, when they try Ecstasy, they don't know how to deal with it, because they didn't learn anything really, and then they fall. If there were a real system of education and support, in which they would teach the children what life really is, then even experimenting with Ecstasy wouldn't cause them to fall. Nobody would be `scratched' by it. Those who have to deal with this must understand that the damage takes place much, much earlier. They didn't talk about that with us in elementary school. Nor in high school . We didn't learn anything. We didn't experience anything. Before the trip, for the first time, I came across the brochures that told me - beware of drugs. Beware of such and such punishments. Really, thanks a lot. Where were you all these years?"

|

|